Even though the state imprisons and sometimes executes citizens trying to flee it, it permits thousands of foreigners to visit every year on tightly controlled tours-one of the few ways its sanction-crippled economy makes cash. And since he would already be traveling to Hong Kong to study abroad, he decided he wanted to witness the world's most repressive nation: North Korea. He had long been curious about other cultures and had previously visited intrepid destinations like Cuba. Knowing that he would soon be laboring over spreadsheets, he decided he wanted an adventure over his winter break.

When he won a finance internship the fall of his junior year, there was no disputing that he was a man fully in charge of his destiny. He joined a fraternity known for its “kind of nerdy dudes,” and one of his college friends said that academics and family always took precedence over everything else, from partying to tailgating at football games.

A meticulous planner, he filled a calendar hung on his dorm wall with handwritten commitments: from assignments to dates to bringing differently abled friends to basketball games. Of course, Otto's best days seemed ahead: He attended the University of Virginia with a scholarship, intent on becoming a banker. He took as his theme a quote from The Office: “I wish there was a way to know you're in the good old days,” he told his peers, “before you've actually left them.” When the time came for him to give a speech at his high school graduation, instead of orating grandiosely, he admitted to struggling to find words. Otto became a symbol used to build “a case for war on emotional grounds,” the New York Times editorial board wrote.īut despite running in the “popular circle given his athletic prowess, classic good looks and unending charisma,” a classmate later wrote in a local newspaper, he “still felt like everyone's friend.” Though his family was well-off, he had a passion for “memorabilia investing,” as he called thrift-store shopping, and sometimes dressed in secondhand Hawaiian shirts. Meanwhile, the American military made preparations for a possible conflict.

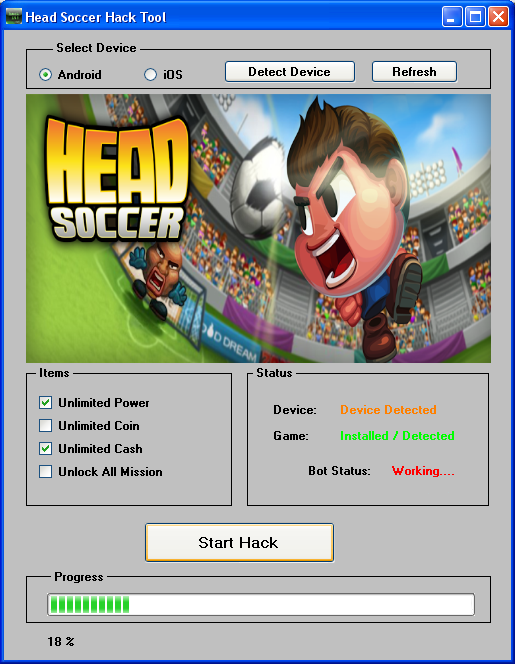

#2017 head soccer hack tv#

Fred and Cindy declared on TV that their son had been physically tortured, in order to spotlight the dictatorship's evil. A senior American official asserted that, according to intelligence reports, Otto had been repeatedly beaten. North Korea blamed Otto's condition on a combination of botulism and an unexpected reaction to a sleeping pill, an explanation that many American doctors said was unlikely. Instead, in the vacuum of fact, North Korea and the U.S. And despite exhaustive examinations by doctors, no definitive medical evidence explaining how his injury came to be would ever emerge. But Otto would never recover to tell his side of the story. She forced herself to join him in the emergency vehicle, though seeing him in such torment had almost made her pass out.Īt the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, the family camped at Otto's bedside while speculation blazed around the world about what had rendered him vegetative. ”īy the time paramedics carried Otto out of the plane by his legs and armpits and loaded him into an ambulance, Cindy had recovered somewhat. It was only later that a member of Otto’s tour group would wonder about “the two-hour window that none of us can account for. “I love you, Otto,” she said, then sang “Happy Birthday.” On her son's 22nd birthday, Cindy lit Chinese-style lanterns and let the winter winds loft the flame-buoyed balloons toward North Korea, dreaming they might bear her message to her son. But I am only human.… I beg that you find it in your hearts to give me forgiveness and allow me to return home to my family.” Despite his pleas, he was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor and vanished into the dictatorship's prison system.įred and Cindy had so despaired during their long vigil that at one point they allegedly told friends that Otto had probably been killed. He sobbed to his captors, “I have made the single worst decision of my life.

One of their last glimpses of him had been from a televised news conference in Pyongyang, during which their boy-a sweet, brainy 21-year-old scholarship student at the University of Virginia-confessed to undermining the regime at the behest of the unlikely triumvirate of an Ohio church, a university secret society, and the American government by stealing a propaganda poster. They had not spoken to their son Otto for a year and a half, since he had been arrested during a budget tour of North Korea. On a humid morning in June 2017, in a suburb outside Cincinnati, Fred and Cindy Warmbier waited in agony.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)